There are plenty of different certifications in the watch world, from the country a timepiece is made to the hallmarking of its precious metals. In an industry where provenance is a big deal, knowing where something is from is non-negotiable (even if it can be a little tenuous at times). So too is performance, with movements going through their own set of qualifications, with organisations like COSC and METAS testing very specific, measurable aspects of chronometric rigour.

There’s one certification however that goes above and beyond the basics of timekeeping. It brings together performance, expertise and place like no other: the Poinçon de Genève.

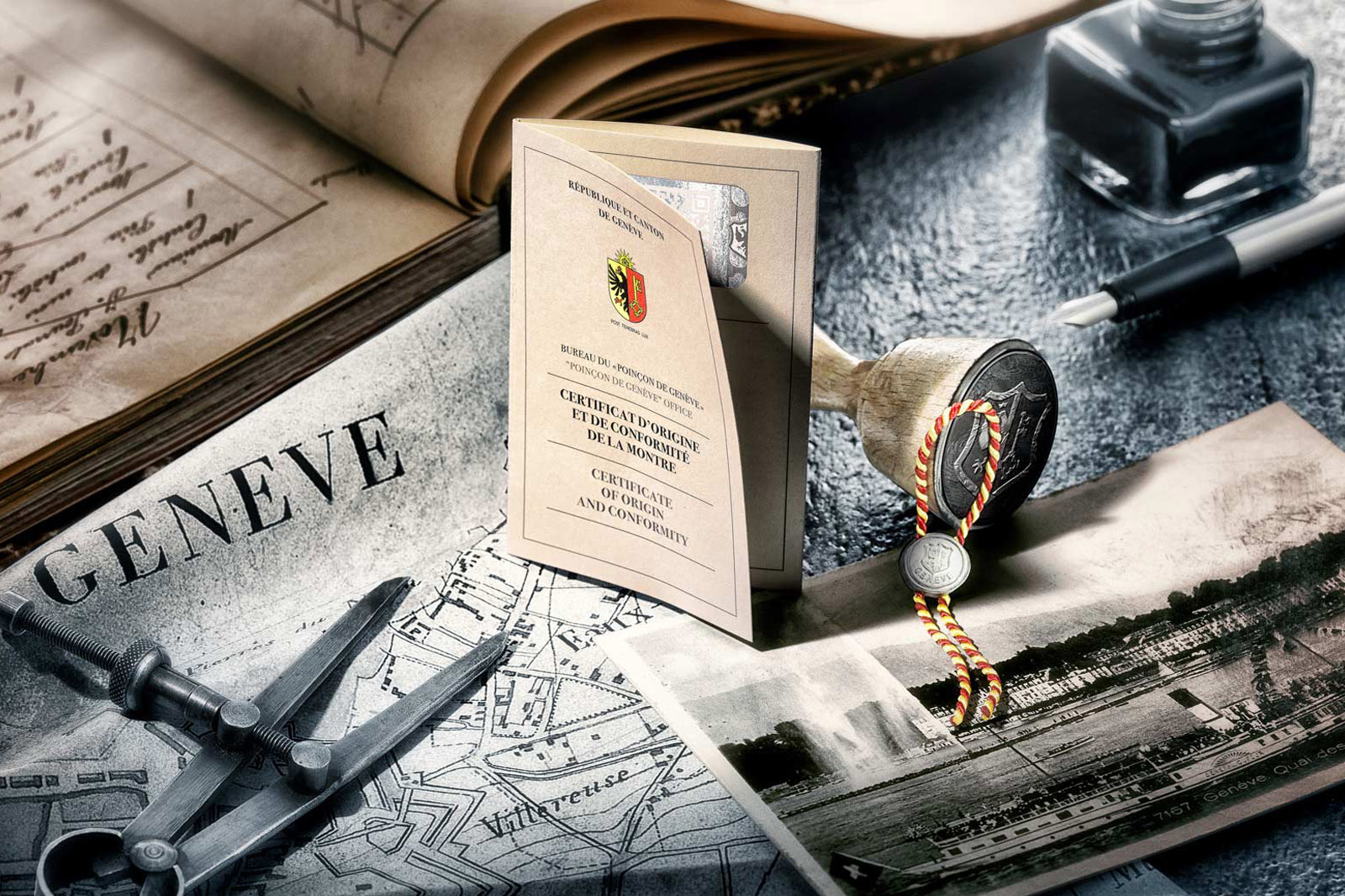

The Poinçon de Genève, or Geneva Seal, if you insist on anglicising everything, has been around for a good long while now. In fact, the seal first came into being way back in 1886 when Switzerland was having a slight issue. These days, the country’s known for watchmaking almost as much as chocolate, but back then watchmakers were moving out of the city and moving abroad. Geneva as a city needed a way to give some gravitas to their watches.

The answer was essentially the watchmaking equivalent of what the French call Appellation d’origine contrôlée in wine. These area-specific classifications denote a bottle not only made in a certain area, but using certain grape variants and traditional methods of production. It’s often a byword for quality without actually saying that. The Poinçon de Genève is much the same.

In order to qualify for the seal, a watch must demonstrate three things. First and historically the most important is that they’re a Geneva-founded watchmaker. This was originally to try and encourage watchmakers to stay in Geneva amid the industry exodus in order to qualify for the seal. As Geneva’s global reputation for watchmaking really took off, it became a nod to quality in and of itself.

Second, they must demonstrate impeccable aesthetics and perfect assembly across the movement components and finishing. This is what is most often associated with the Poinçon de Genève. The general idea here is to remove any sign of machining and leave only handmade artisanry.

So, edges are bevelled and polished, wheels and other flat surfaces are circular grained or finished with perlage and bridges have all traces of machining removed. They may be useful for trapping dust, but this emphasis on hiding the machine work is historically the main use of Côtes de Genève, or Geneva Stripes. Even the sinks for ruby bearings have to be polished, and the jewels themselves ‘semi-brilliant’ so a feature all their own. In short, if any visible machining remains on any component, it’s disqualified.

Until relatively recently, the Geneva Seal stopped there, with a focus entirely on the finishing. But in 2011 and 2014, the requirements were updated with reliability criteria. 2011, incidentally, was when the seal was updated to include the entire watch, not just the movement. Between them, those changes meant a much more demanding set of hoops to jump through and coincided with Timelab’s takeover of the testing in 2010.

Timelab is a big mover and shaker in the Swiss watch world. Founded in 2008, they were tasked with taking over Contrôle Officiel Suisse des Chronomètres meaning that any time you hear of COSC-certified, it went through them. Needless to say, they have some experience in the field of performance testing.

As to what that testing entails, it’s mostly just auditing what watchmakers say they’re making. For water resistance, every watch is tested to at least -0.5 and +3 bar, so half an atmosphere and three times atmosphere, or 30m underwater. If the water resistance is claimed to be higher, it’s tested to that instead. The same sort of thing goes for power reserve and functionality, too. If the watch does what its maker says it can for as long as they say it can, it passes.

Vacheron Constantin calibre 3200

As you’d hope, accuracy testing for the Poinçon de Genève is a little more concrete. It’s tested for seven days solid. Manual-wind watches can be wound every 24 hours; automatic watches must rely on their automation. Readings are taken at the start of the week and again on day seven, and if it’s out by less than a minute at the end – compared against a reference clock – then it can pass.

Now, this all makes the accuracy testing here far less exhaustive than COSC. You might think that it’s due to the full watch, rather than just the movement being tested, but METAS does that too and it’s far more extreme. The bottom line is simply because, while reliability is an integral part of a Genevan watch, at this level it’s much, much more about the craftsmanship.

So, who actually qualifies for the Geneva Seal? By limiting the pool to brands with watchmaking based in Geneva, recipients are limited by nature. In fact, there are only five that currently put their watches through Poinçon de Genève testing: Cartier, Chopard, Roger Dubuis, Vacheron Constantin, and Louis Vuitton.

Vacheron Constantin Historiques 222, with the Geneva Seal stamp on the caseback

You might be wondering, why not Patek Philippe? Well, they used to enter their watches, but in 2009 decided instead to set up their own testing that included gemsetting among other things.

Personally, any maison that relies on in-house testing feels a little dodgy to me, but if you can’t trust Patek Philippe, then who can you trust? What you can certainly trust is that any watch stamped with the Geneva Seal is not only accurate and reliable, but a masterclass in excessive, handmade finishing, which is really what high-end watchmaking is all about.

Cartier, Chopard, Roger Dubuis, Vacheron Constantin, Louis Vuitton, and Ateliers deMonaco are currently the only watchmakers based in Geneva that qualify for Poinçon de Genève testing, while Patek Philippe do their own testing in-house.

More details at Poinçon de Genève.

Oracle Time